by Randall Carlson

“As every dam engineer knows, water also has one job, and that is to get past anything in its way” David Macauley, Building Big, 2000.

I have written in another article about a potential disaster that could occur in Iraq if the Mosul Dam fails. I described the conditions of the dam built during the regime of Saddam Hussein on the Tigris River and the circumstances which has brought it to the brink of collapse.

Assuming that the dam fails catastrophically, which it would be likely to do if it failed at all, 2.7 cubic miles of water will be rapidly introduced into the Tigris River Valley almost instantaneously. That is a lot of water. A massive flood surge will sweep downriver at a rate of about 10 miles per hour, although, initially, much faster. It will travel roughly 40 miles by river from the dam breakout point to the city of Mosul in about 4 hours. The wave could be over 70 feet high as it reaches Mosul. 22 hours later the wave, by now reduced to about 50 feet high, will reach Tikrit, the hometown of Saddam Hussein. 400 miles downriver from the dam is the City of Baghdad. When the flood hits Baghdad, about two days after dam failure, the surge will spread out inundating some 80 square miles of the city, with large sections near the river − the very heart of city − under 13 feet of water.

The death toll, not only from the flood itself, but also from the chaotic aftermath, could be a million people or more. The flood would likely knock out Iraq’s electrical system and cause severe effects on agriculture, which is practiced extensively in the fertile bottomlands of the Tigris Valley. There will be a massive population displacement. The flood wave will sweep all before it: cars, trees, wreckage of buildings, corpses of humans and animals, unexploded ordinance. The archaeological tragedy will also be profound. The ruins of ancient Ninevah among other sites, lie in the path of the flood.

All this should the dam give way.

On February 29 of this year (2016) the U. S. Embassy in Iraq issued a warning, calling the situation “serious and unprecedented.” On Tuesday, March 8, U.S. Central Command briefed the Senate Armed Services Committee on the developing situation. General Lloyd Austin III stated to the committee that “if the dam fails, it will be catastrophic.” On Wednesday, March 9, after a briefing at the United Nations, Samantha Power, U.S. Ambassador to the U.N. echoed General Austin’s opinion that a dam failure would be catastrophic and called upon U.N. member nations to lend their support, tweeting: “Work to stabilize Mosul dam must begin ASAP but all countries must step up to fund relief & public education on evacuation routes,”

Another one of the original engineers who worked on the dam, Nadhir al-Ansari, told Newsweek magazine that with spring warmth snowmelt will significantly increase the pressure on the already weakened dam. “In April and May, there will be a lot more snow melting and it will bring plenty of water into the reservoir,” he said. “I don’t think the dam will withstand that pressure.” As I write these words U.S. and Iraqi officials are working on a plan to evacuate up to 1.47 million people—the same plan that Nasrat Adamo called “ridiculous.”

Since that article was written in May, the Iraqi government has contracted with an Italian company to commence urgent repairs, which however, are yet to begin. On the upside one of the sluice gates is working and the reservoir is at present about 36 feet below full pool. But the condition of the bedrock below the dam is highly problematic and grouting operations are now underway. This process involves drilling boreholes into the porous bedrock and injecting up to two tons of concrete per day to prevent seepage, which if allowed to continue would quickly erode the limestone and gypsum bedrock to the point of failure.

If this dam fails the world will be confronted with a tragedy of epic, near biblical proportions. But it will also be presented with a lesson in mega-scale hydrology that, by extrapolation, could allow modern humankind a real sense of the scale of world-destroying floods experienced by our ancestors in prehistoric times. However, it would be far better to derive whatever lessons are to be gleaned from this unfortunate situation by informed conjecture and computer models than to witness the possible death of more people than have been killed throughout the entire Iraq war. We will just have to wait and see what the outcome of this situation will be. Hopefully the Italian team can begin desperately needed repairs in time. If the dam holds through the spring run-off season there is a good chance of averting catastrophe by buying an extra year of time.

So here we are talking about a man-made flood, which, if it were to occur, would undoubtedly be one of the great humanitarian disasters of modern times. It is in the pondering of such a scenario that the sense of urgency wells up to do whatever it takes to stave off a tragedy of such magnitude. But, it should also provoke us to consider further the role that great fluvial catastrophes have played in human history and to seek after the causes of phenomenon such as mega-scale floods that are measured in millions to hundreds of million cubic feet per second.

It is of no small significance that most nations and cultures of the world have deep rooted myths of tremendous floods, which, if taken literally are clearly beyond the scope and scale of anything that can be referenced from modern experience. In the essay Cosmic Lessons: Burkle Crater, Noah’s flood and the Mosul Dam, I presented evidence for a natural event capable of generating a tsunami flood of enormous magnitude in the vicinity of the Indian Ocean and the Persian Gulf, one capable of drowning any civilization inhabiting the lands adjacent to the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. I have presented some considerable evidence in support of this possibility, but, only further challenging field investigation will yield up the proof. I have discussed the work of Dallas Abbott and her colleagues that indicates the possibility of a large bolide impact into the Indian Ocean capable of generating a tsunami of sufficient magnitude to cause widespread destruction. A tsunami as envisioned would leave marine deposits in its wake. Such deposits found in the sediment of the Tigris Euphrates plain would be powerful confirmation that such an event actually took place.

While an event such as a 1 or 2 mile wide meteor striking the Indian Ocean in the vicinity of the proposed Burkle Crater would undoubtedly generate tremendous devastation in the region, would it be of a magnitude sufficient to spawn legends of world destroying floods among Eskimos in the Bering Straits, or Native American tribes from the Atlantic to the Pacific Oceans, or the Mayans of Central America, or divergent indigenous peoples from Amazonia to Siberia, amongst numerous others? The answer is probably not. However, it is becoming apparent that events on a scale far beyond anything experienced in modern times, including extreme mega-flood events, have been a regular part of Earth history, up to an including the span of time that modern humans have occupied this planet.

It turns out that an enormous amount of detailed information can be extracted from the various tales, legends and myths that constitute the legacy of ancient times − when considered in the light of modern knowledge of the planetary and astronomical environments. To this belief in floods on a scale almost supernatural I will return in another essay, after first examining some floods of a lesser magnitude that have been part of recent human experience. These modern floods, through diminutive compared to their ancient counterparts, can, nonetheless, impart tremendous insight into the nature of gigantic paleofloods and the recognition of their effects in the planetary landscape.

At present only a handful of researchers are fully cognizant of the profound and far-reaching implications of the convergence of geology, mythology, archaeology and history that is now underway. But the paradigm is shifting and a much vaster and deeper view of the story of humankind on Earth is emerging. Recent and historical catastrophes that have been observed and documented can provide powerful insight into the nature of ancient catastrophes for which only myth and legend remain. Modern events, though of a smaller scale, nonetheless serve as potent analogies for understanding similar events from the past and aid in the recognition of the effects in the geological record.

One of the foundation principles of modern geological science is the principle of Uniformity, or Uniformitarianism, which can be summarized quite succinctly by the well-known phrase: “The present is the key to the past.” The idea is that phenomenon throughout the course of time are similar, that the laws of physics as we understand them hold constant, and that processes operating on the Earth today are similar to, or even identical with processes that occurred the past: i.e. the way water erodes the rock today is similar to the way water would have eroded rock eons ago. This is an extremely powerful analytical tool to facilitate understanding of events that transpired long before science was present to observe, but a problem arises when the principle is applied dogmatically under the assumption that phenomenon of the past was always on a scale and magnitude, or rate similar to that of today, which, we now know, is most certainly not the case. I hope, however, to apply the principle of Uniformitarianism in the manner for which it was intended, as a tool for decoding the geological record imprinted into the landscapes of Earth. So to that end, to more effectively understand great catastrophes of the past, we shall endeavor to understand modern catastrophes as an analog, again, keeping in mind that modern events are diminutive compared to their ancient counterparts.

Turning to North America we find a striking example of this juxtaposition of ancient and modern events involving catastrophic floods. In this case the flood was not merely potential, as is the case with a possible Mosul Dam failure, but actual, it did, in fact, happen. We have photos, videos, eyewitness accounts and in depth investigations that occurred in the immediate aftermath of the catastrophe, and we have the evidence of the field, demonstrating the effects of violent torrents upon the landscape. Very few Americans remember this event that occurred 40 years ago, in June of 1976, the last great dam disaster in the United State and the cataclysmic flood that ensued. This was the Teton Dam collapse that occurred with the failure of a newly constructed earth fill dam built in the headwaters of the Teton River, a tributary of the Snake River in eastern Idaho. The dam, 305 feet in height and 3200 feet in width at its crest, failed as its reservoir was being filled for the first time. The flood discharge just below the dam break out point was at least 1 million cubic feet per second, or greater. The largest flood of record on the Teton River was measured at 7000 cubic feet per second, which means that just below the dam breach the flow was about 150 times greater. The story of the dam collapse and ensuing flood is a truly remarkable one for many reasons and is worthy of further inquiry and consideration.

Similar in some respects to the flood story from the Middle East and the potential Mosul Dam failure in that region, there was also a great natural flood, a flood of considerably greater magnitude that occurred in prehistoric times near the same region as the modern Teton Dam flood. I will discuss this extraordinary flood in detail in another article. Suffice it to say, as far as this ancient flood goes, that at the end of the last ice age there was a weak sedimentary rock dam in a mountain pass close to the northern Utah, southern Idaho border. Behind this dam lay massive Lake Bonneville, a lake that was more of an inland sea than a lake, covering almost 20 thousand square miles during the later days of the most recent ice age. Modern day Great Salt Lake is but a minute remnant of this mighty ancient lake. At some point as the Great Ice Age came to its convulsive conclusion between about 13 and 14 thousand years ago, this dam gave way and a 300 foot deep torrent of water spilled over the divide and onto the Snake River plain. This flow was at least 20 to 40 times greater than the peak flow of the Teton Dam flood, and unlike the Teton flood whose peak discharge was only sustained for several dozen miles, this flood tore across more than a thousand miles of southern Idaho with no diminution in power, with sustained discharges approaching 40 million cubic feet per second. A scour trough gouged out by the torrent as it discharged out onto the Snake River Plain is now occupied by American Falls Reservoir. A consideration of the Teton Dam flood disaster provides a valuable analog for those larger scale prehistoric events that have swept over large regions of the Earth’s surface from time to time.

To reiterate some key points developed so far in these recent articles: I have discussed potential flood disasters in the Middle East, both ancient and modern. I have speculated, with some degree of confidence, that behind the tales of gigantic, world destroying floods emanating from the ancient Middle East, there was a real deluge event of extraordinary magnitude triggered by a bolide impact into the Indian Ocean. I have presented substantial evidence supporting this conclusion. I have introduced a concept I call time-transgressive juxtaposition, referring to phenomenon of a similar or parallel nature occurring in the same geographic region but separated in time, producing an “overprint” effect, a superimposition of effects upon the same landscape. As an example I described the circumstances surrounding the Mosul Lake Dam and the possibility of an extreme disaster should it fail, thereby causing a disastrous flood along the Tigris River valley with the potential to kill hundreds of thousands of people and how this echoes the vast legendary inundation of the same region thousands of years ago preserved in myth, legend and holy writ. A flood of this magnitude would leave definite imprints upon the

landscapes over or through which it passed. So to what extent is there evidence of a major hydrological event in the Middle East from a time period that might be consistent with chronologies derived from the various legends? Only further research will confirm or refute such a conclusion but it ought to be said that hard geological evidence continues to accumulate for the occurrence of at least one vastly destructive flood in the Middle East since the end of the last ice age. To this critically important story I will return in another essay.

Before leaving the discussion of the Middle East and turning closer to home I would note that since I began writing this article I have learned that the team of specialists from Italy has finally been dispatched and is now undertaking emergency measures to stabilize the precarious dam. Hopefully their efforts will be successful. Meanwhile the Islamic State (IS) is terrorizing the inhabitants of nearby Mosul, sealing off all outlets out of the city and brutally punishing even the slightest infractions of their version of Islamic law. However, the word from escapees and refugees is that the population is turning against them. It appears that with the U.S. led offensive to retake Mosul the volume of news has diminished, with few reports on the dam’s status appearing since mid-April.

I am grateful that the Mosul Dam has not failed, so far sparing the world an immense humanitarian catastrophe. But to the dam that did fail I would now direct your attention to see what insight may be acquired relative to understanding events of long ago.

Here is what happened: In America’s Bicentennial Year of 1976 the newly built Teton Dam in Idaho failed, unleashing a massive torrential flood into the headwaters of the Snake River. This was the last great dam disaster in America and effectively pulled the plug on the Federal Bureau of Reclamation’s program of monumental dam building that had been going on for some 75 years. James Sherard, one of the post failure investigating engineers, was quoted as saying: “the Teton Dam failure is one of the most important single events in the history of dam engineering.” At a meeting of the House subcommittee investigating the Teton Dam collapse, Congressman Leo J. Ryan of California, heading up the congressional investigation of the catastrophe, called it “one of the most colossal and dramatic failures in our national history.” The story of this event deserves a wider telling than it has received for its lessons are many. Like the current predicament of the Mosul Dam, the failure of the Teton Dam was the result of a confluence of human errors and has a peculiar connection to another kind of humanitarian catastrophe that happened just over two years later.

Before delving deeper into the details of this American dam disaster, I would take a short tangent and mention something about Congressman Ryan whom I quoted above. As some older readers may recall, Ryan was shot to death in Guyana in November, 1978, by members of the Peoples Temple, the fundamentalist religious cult founded by Reverend Jim Jones that was, at the time, the subject of a Congressional investigation being led by Ryan. The Congressman, along with three journalists and a defector from the group had visited Jonestown, the community founded by the People’s Temple in the jungles of Guyana. As they attempted to leave the country from a local airstrip they were attacked by members of the group and a

gunfight ensued. Ryan was killed along with the three journalists and the defector. The following day Jones, and over 900 members of the group committed mass suicide by drinking cyanide laced Kool-Aid. (Actually Flavor-Aid) The lessons to be gleaned from this incident, and the events leading up to it, are extensive and worthy of further consideration but this is not the place for that undertaking. Suffice it to say that the Reverend Jim Jones was an avowed Marxist and the emigration to Guyana from California was for the purpose of setting up a socialist utopia. All members of the Temple were expected to surrender their individuality, and hence their humanity, to the good of the group, (and, of course, its leader) and this they did to its extreme and disastrous culmination, although, at the end many of them, no doubt, had second thoughts, but by then it was too late. What the members of the Peoples Temple did was to follow the logic of collectivism to its tragically inevitable conclusion, and whether you call it Marxism, Communism, Fascism, Socialism, or Statism, does not matter, the result is that the value of an individual life is subordinated to that of the group and has no worth apart from the group and its abstraction, the “State.” And, as is always the case, this devaluation of the individual and of individual rights is undertaken in the name of equality and social justice. The perverse consequences of a collectivist belief system are now being experienced firsthand by the citizens of Guyana’s neighbor, Venezuela, as the socialist paradise of Hugo Chavez collapses before our eyes.

In the case of the Peoples Temple, with an extreme example of the abdication of one’s individuality, we can discern a parallel to disasters of a purely natural origin, in that both are the result of a certain pattern of confluent forces converging at a critical node. As it was with the mass suicide of the members of the Peoples Temple, so it is with the economic catastrophe that now befalls Venezuela, so it was with the great natural catastrophes of Earth history, whether of endogenic or exogenic origin, and so it was with the Teton Dam disaster. All catastrophes are the outcome of, and are preceded by, a pattern of events unfolding in space and time. Discernment of these patterns forms the basis of prophecy.

But I digress. Returning to the story of the Teton Dam and the valuable lessons it has to impart I will now briefly describe the events leading up to the disaster, the collapse of the dam, and the aftermath, keeping in mind that the entire series of events was initiated as a result of political choices and priorities.

PRELUDE

Like the Mosul Dam, the Teton Dam was an earthen embankment structure and, like the current dangerous predicament of the Mosul Dam, the failure of the Teton Dam was the result of the cumulative effect of human error. The multiple purposes for which the dam was being built included agricultural irrigation, flood control, power generation and recreation. Investigations of the Teton River canyon for purposes of dam construction go back to the early 1930s. An impetus to undertake construction of a new dam came in the wake of a severe drought in the region in 1961 followed by a major flood the next year. The Bureau of Reclamation proposed the construction of a dam in 1963 and Congress authorized the funds the following year. After extensive surveys and core sampling throughout the 1960s, a site was chosen in the lower Teton Basin in Fremont County, Idaho. (The coordinates of the site are 43° 54’ 33” N latitude x 111° 32’ 24” W longitude) Again, I will highly recommend the use of Google Earth as a research tool. The wreckage of the dam shows up clearly as does the downstream region affected by the flood. All one needs to do is type Teton Dam in the search engine and Google Earth will zoom right in on it.

Construction of the dam began in February of 1972. Specifically, the dam was constructed of five zones of different kinds of earth material installed in compacted layers, each layer performing a different function with the central core designed to be the one that actually retained the water. As I stated, at completion the dams crest stood 305 feet above the riverbed and its width was almost 3200 feet. At the base of the dam it was 1700 feet wide. When full the reservoir would have contained 356 million cubic meters of water, equivalent to about 94 billion gallons and the lake formed above the dam would have reached upriver nearly 17 miles. One way to visualize this volume of water is to imagine it frozen as a giant ice cube. In this case the cube would be about 2350 feet on each side (disregarding an expansion coefficient for ice.) That’s a lot of water. Given that one cubic meter of water weighs one metric ton, it is obvious that the weight of the lake when full would be some 356 million metric tons. That is a considerable amount of pressure bearing on the bedrock. (By comparison, if the volume of water in Mosul Lake reservoir were frozen into a giant ice cube, it would be more than 7,300 feet on a side, or 1.4 miles.) While a number of geologists and engineers had expressed reservations about the Teton site and the unsuitability of the bedrock for dam construction, politics took precedence over prudence and the project went ahead anyway.

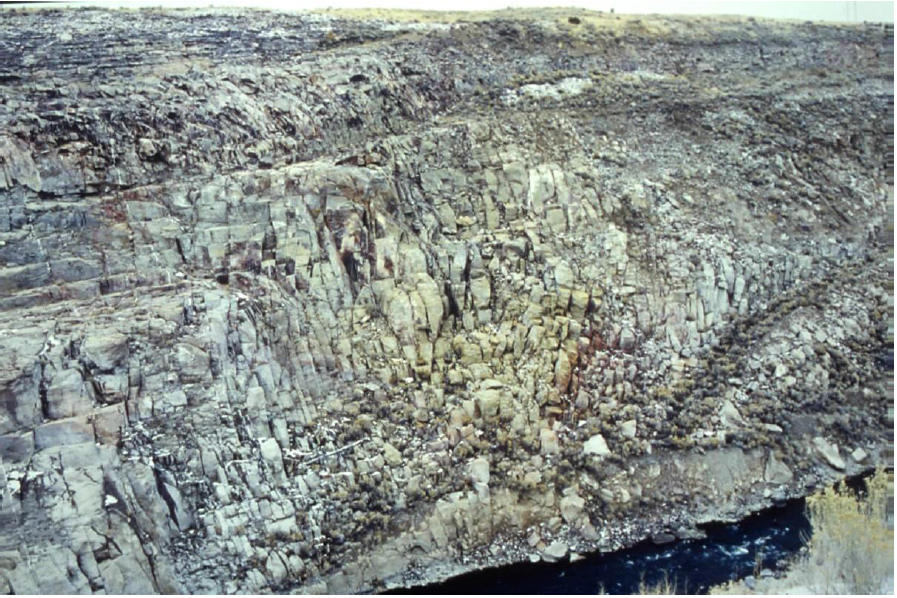

The main problem with the bedrock in the Teton Dam locale is that it consists of porous rhyolite and basalt. These are volcanic rocks which any geologist will advise are not the kind of foundation upon which one wants to erect a major dam with a large reservoir behind it. Interestingly, this particular rock, called by geologists the Huckleberry Ridge Tuff, was the product of a massive eruption of Yellowstone Caldera about 2 million years ago. This violent eruption was at least 6000 times more powerful than the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens, ejecting about 600 cubic miles of dust, ash and debris into the atmosphere. This amount of ash would have produced a severe environmental effect that would have been brutally disruptive to both the global climate and the biosphere. Here is a striking example of a juxtaposition of catastrophes, a superimposed imprinting of the effects of a modern hydraulic event upon a landscape created by a flood of ash and molten rock emanating from within the Earth. When this material cooled it formed an extensive array of fractures and fissures. This character of the bedrock is clearly displayed in the Figure 1.

Figure 1. Extreme fracturing of the bedrock is clearly displayed in this photo of the right abutment area before construction of the dam. Extensive voids were uncovered during the process of excavation. The rock is a type of rhyolite called welded tuff that forms through the lithification of volcanic ash flows. It is NOT a suitable bedrock for construction of a large dam and reservoir.

So, the bedrock into which the Teton Canyon had been eroded was composed of this highly fissured and porous rhyolite and basalt. The choice, therefore, of dam site itself was the first mistake. The problem was that sites suitable for the construction of monumental dams were becoming scarce by the 1970s at the same time as pressure from multiple factions lobbying for all the presumed benefits to be derived from the new dam were considerable. I should mention that up to this point the Bureau’s record of dam building over nearly 75 years was virtually impeccable, without a single dam failure (although one close call). The engineers, geologists, contractors and other professionals in their employ were highly experienced at dam building, after all, the Bureau had built two of the great engineering wonders of the modern world, Hoover Dam and Grand Coulee Dam. But this reign of success and accomplishment became compromised as the enterprise became progressively more bureaucratized and politicized with the growth of government. Teton Dam represented the tipping point and its physical collapse parallels the economic collapse in Venezuela as that nation succumbs to total bureaucratization. As I mentioned, the failure of Teton Dam marked the end of the era of monumental dam building in America.

Over the basalt bedrock of the region there has accumulated a very interesting and unique type of soil material called loess (pronounced ‘luss’). This mostly volcanically derived soil is extremely fertile and is widely distributed throughout the Pacific Northwest. All that is needed for loess to support abundant biological activity is the addition of water, but much of the area over which it is found in Idaho and Washington is quite arid, hence, the numerous hydrological projects undertaken throughout the northwest by the Bureau of Reclamation that occasioned the building of dams, canals, aqueducts and irrigation systems. The annual precipitation in the headwaters of the Snake is less than 20 inches per year and most of this comes in the form of snow. I will have more to say about this curious loess material as well as the Yellowstone caldera eruptions in future contributions, but for now we will note that due to the local abundance and accessibility of loess, which happens to be a very friable substance, it was chosen as the core material for the Teton Dam. In fact, the origin of the term loess is a German word that means loose and from which the English word derives. The decision to use abundantly available loess material was the result of cost saving efforts which was in turn due to the insufficiency of available funds to construct the dam correctly. I will comment further on this matter below. The choice of loess for the core material was mistake number two.

In the course of site preparation contractors began grouting operations. As I explained in the article about Mosul Dam in Iraq, grouting is a method of injecting fluidized concrete under high pressure into voids and fissures in the rock surrounding a dam for the purposes of preventing seepage. When the grout hardens it forms an impervious barricade to water penetration, or at least that is the working assumption. In the course of excavation it was confirmed that the bedrock adjacent to the Teton Dam site was porous, containing large voids and cavities, some of which consumed enormous quantities of grout. In some cases the voids were never actually filled. Some of the grout holes extended to a depth of more than 300 feet. Large fissures and caverns were especially prevalent around the right abutment. More than 1.1 million cubic feet of grouting material was injected into the Swiss cheese like bedrock with no end in sight. This was more than double the amount of grout originally estimated. The decision was made to suspend grouting operations due to the accruing cost overruns. This was mistake number three.

In early June of 1973, the contractor, Morrison-Knudson, completed the diversion tunnel and rerouted the Teton River on June 8. Emplacement of the embankment material commenced in October, 1973. The embankment, as I said, consisted of five layers with the central core layer, the one that was to serve as the barrier to water penetration, composed of friable loess. Over the loess core were layers of rock and clay extracted from the site and from borrow pits nearby. At its completion the Teton Dam consumed some ten million cubic yards of earth and rock material.

Figure 2. The Dam as it looked nearing completion in May, 1976. The view is toward the right abutment where the breach occurred. Source of photo: Rogers, J. David (?) Retrospective on the Failure of Teton Dam near Rexburg, Idaho June 5, 1976. Missouri University of Science and Technology: Teton Dam Failure, slide show

By the beginning of 1976 the dam was, for the most part, complete. Officials had already begun filling the reservoir in October, 1975. The approved filling rate for a large dam reservoir was generally not permitted to exceed a maximum rise of about 1 foot per day. This allows the site to adjust slowly to the substantially increased pressure imposed by the weight of a large body of water. However, in the spring of 1976 two occurrences conspired against this preferred filling rate. First, there was an unusually heavy snowpack on the Teton Mountains that winter, and second, the month of May was unusually warm. The warm weather triggered a rapid melting of the copious volume of snow which had accumulated and that caused a rapid rise in river level. The decision was made to capture the increased amount of meltwater, thereby accelerating the filling of the reservoir and hence, the completion date, for the project was significantly behind schedule due to the numerous delays arising as a result of the highly problematic site preparation. So the reservoir was allowed to fill at its natural rate rather than a controlled rate. This led to a water level rise over four times greater than the recommended rate. A process that should have taken up to three years was virtually completed in that single spring of 1976. What compounded the problem of the accelerated lake level rise was the fact that the outlets by which the water level could be drawn down were only partially operational. So this was major mistake number four.

Figure 3. Figure 3. Aerial photo of Teton Dam as it was nearing completion, taken September 26, 1975, before the filling of the reservoir. Star marks approximate position near the right abutment where the leak began. Note the power and pumping station at the base of the dam. Source: After Teton

Figure 4. Teton Dam looking downstream. Photo taken ca. May 21, 1976, 16 days before failure. Source: National Archives Catalog. Note the Snake River Plain beyond the mouth of the Teton River Canyon. Failure occurred near the boundary between the embankment and the abutment on the right side of the dam looking downstream. Arrow points to right abutment.

COLLAPSE and FLOOD

In the first few days of June, 1976, as the reservoir reached about 280 feet in depth behind the dam, about 30 feet below the dam crest and about 15 feet from the overflow spillway, several springs showed up downstream from the dam, indicating that water was leaking through its bedrock base. Early in the morning of June 5, a Morrison-Knudson worker arrived at the site to find a leak in the dam itself, about 15 feet above the stream bed close to where it abutted the right canyon wall as one was looking downstream. The measured rate of leakage was about 20 to 30 cubic feet per second. The time of the discovery of this leak was between 7:30 and 8:00 a.m.

This was the beginning of the end for the Teton Dam.

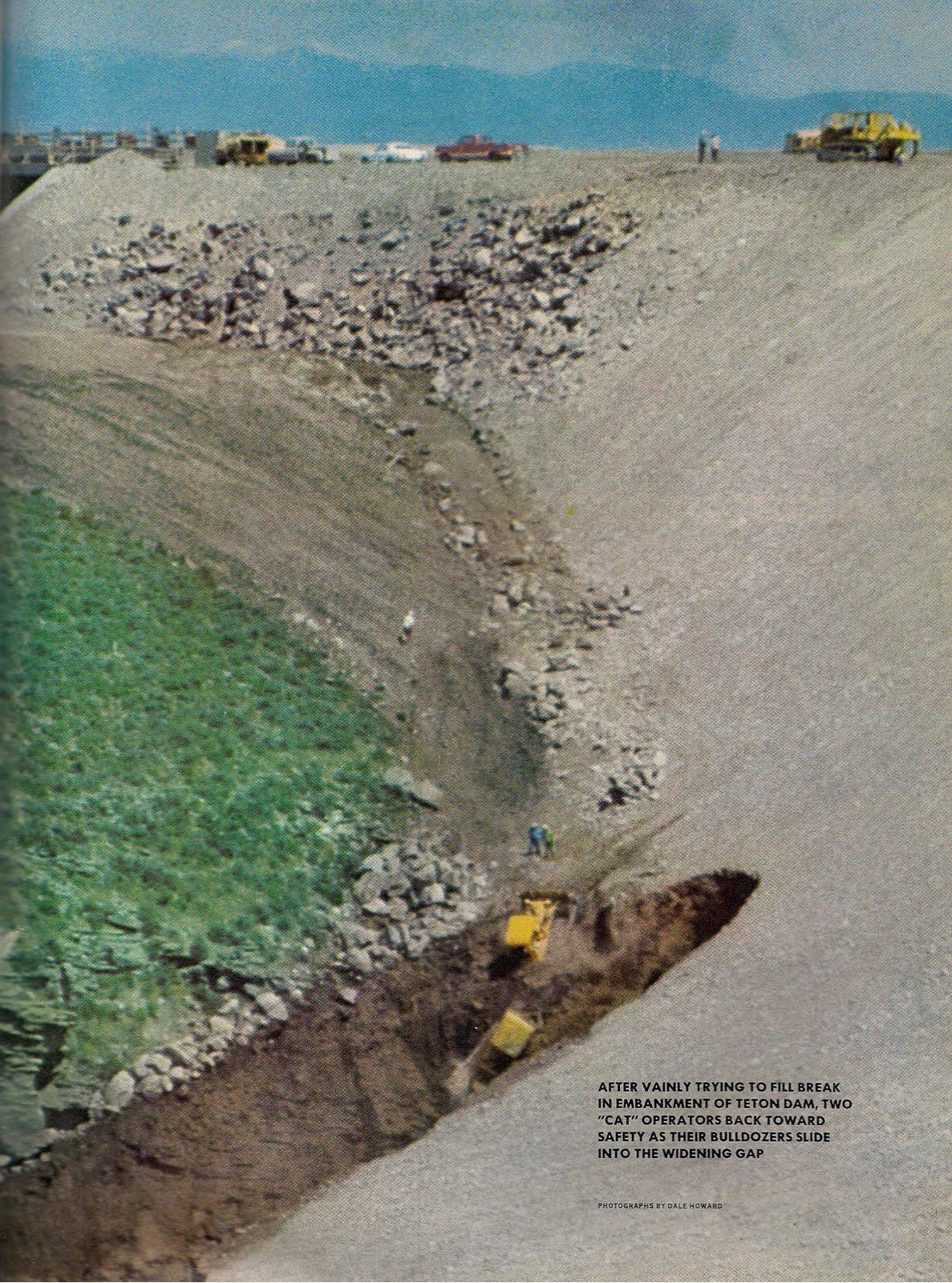

Around 9 a.m. the project manager, Robert Robison, made a closer inspection of the leak and discovered that its’ flow rate had increased to nearly 50 cubic feet per second. He also noticed a second smaller leak issuing from the abutment rock near its contact with the embankment, about 130 feet below the crest. Sometime between 9:30 and 10:00 a.m. a wet spot appeared on the downstream face of the dam no more than about 20 feet from the abutment. The wet spot quickly turned into active seepage and a hole appeared. At this point it was clear that action must be taken. As the hole was growing larger two bulldozers were dispatched to push boulders and material into the hole but it continued to erode faster than they were able to fill it.

Figure 5. Image taken about 10:45 a.m. The wet spot has turned into a substantial leak and the muddy water is beginning to enter the valley downstream. The pumping and power stations are still unscathed, but not for long. Arrow points to a bulldozer making its way toward the leak.

At 10:33 a.m. Teton Dam project officials alerted the Sheriff’s offices of both Madison and Fremont Counties to begin preparing for the onset of a devastating flood in the downstream area. At about 11 o’clock a.m. one of the dozers started to slide into the hole. The second dozer operator worked frantically to pull it out but his effort was futile, for the hole enlarged as fast as the first dozer could be pulled back. Finally both dozers slid into the expanding hole and were swept away into the torrent.

Figure 6. Source: http://rossshirley.blogspot.com/2011/03/teton-dam-disaster.htm

Sometime between 11 and 11:30 Project officials called the Sheriff’s offices and informed them that people living in the flood path must be evacuated immediately. As the call was being made a whirlpool appeared in the reservoir just upstream of the swiftly expanding leak. Two more bulldozers made a frantic and futile effort to shovel rip-rap into the whirlpool but it was sucked down as fast as they could dump it in. The whirlpool quickly expanded from a few feet in diameter to about 20 feet as the hole in the dam face continued to grow.

Figure 7. Image taken about 11:20 a.m. of the rapidly expanding hole. The water is rising against the walls of the pumping station.

Figure 8. The hole has continued to enlarge, eating its way back into the mass of the dam. Here it is about to breach the dam crest.

Figure 9. The dam crest has been reached. The leak has turned into a turbulent rush of muddy water that is now overwhelming the structures below.

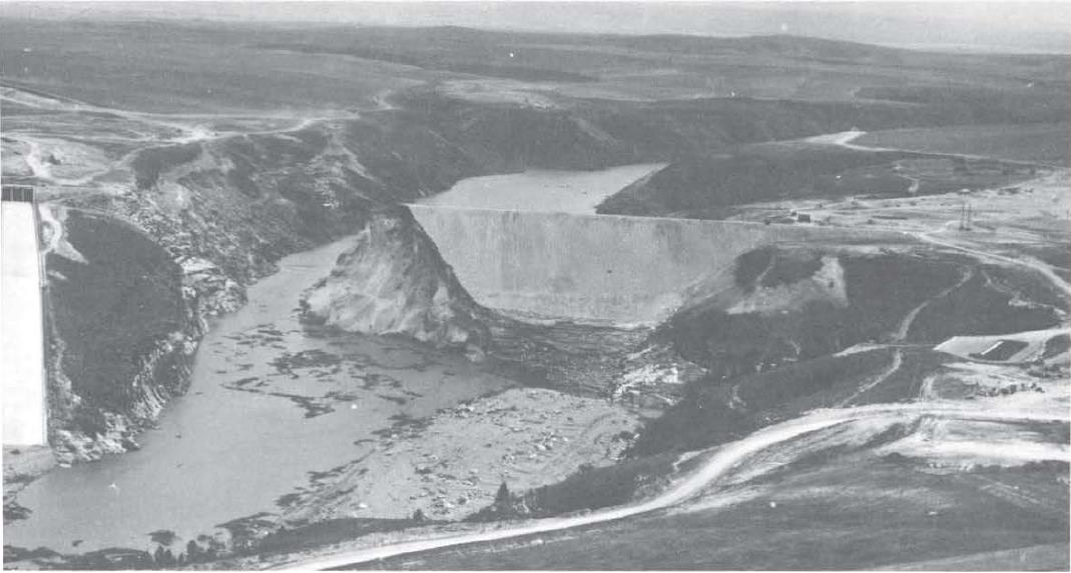

At about 3 minutes before noon a large section of the dam crest gave way and a massive wall of water poured through the opening. The roiling torrent of some 80 billion gallons carried away about 4 million cubic yards of embankment material that now mantles the floor of the canyon for miles downstream. The pumping station and power house at the base of the dam were completely obliterated and buried by the mass of water and mud.

Figure 10. A large section of the dam has collapsed and a powerful torrent of sediment chocked water rushes through the gap. The power station and pump house have been buried beneath the mass of mud and water.

Time magazine for June 21, 1976 ran a story recounting the experiences of a family who witnessed the entire collapse from start to finish. Dale Howard was a geography professor at Minot State College in North Dakota who visited the site that Saturday morning with his family. While he was snapping pictures from an observation platform he noticed “that darn hole started growing—quite slowly at first—forming a small waterfall down one side. It still looked like just a minor leak.” As Howard continued shooting the collapse began to unfold before his eyes and he was able to record the color pictures documenting the progressive failure as shown in Figures 5 through 9. When the two bulldozers were sucked into the hole it became apparent that Howard and his family were witnesses to something truly extraordinary. He commented “My wife was excited and my kids were crying because they thought the world was coming to an end. It was really frightening. If I had had a weak heart, maybe it would have stopped.” He continues his account: “The hole was enormous, and huge chunks were breaking off . . . By this time you could see daylight through the hole. It was almost like a natural bridge. Then the whole thing fell, and it was a raging torrent.” Howard goes on to describe that when this raging torrent hit the power plant “it just disintegrated. The water picked up a huge oil tank like a cork and away it went. There was a beautiful grove of cottonwood trees down below, and they were snapped off like matchsticks. Later I could see the water out on the plain. It was almost like a surrealist picture.”

Figure 11. Aerial view of the dam breach at peak discharge Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/waterarchives/5811723977

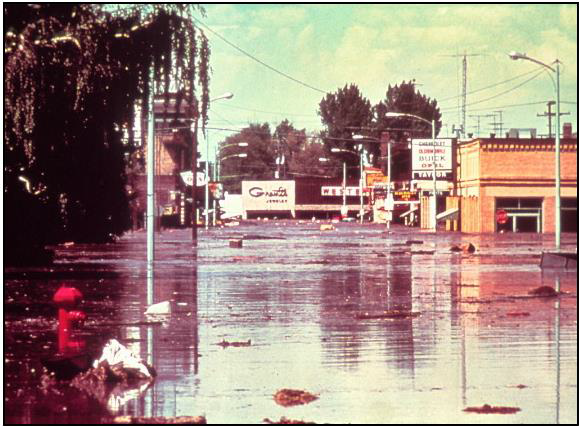

As the torrent of water surged downriver residents of the towns lying in its path – Sugar City, Teton and Newdale – scrambled to evacuate, having to leave in such a rush that most of their belongings were left behind. Luckily, Teton and Newdale were on higher ground and spared the worst ravages of the flood wave. Another town, Wilford, did not fare so well, receiving the full force of the flood it was literally wiped off the face of the map. When the surging flood wave reached Sugar City at about 1 o’clock it was 15 feet deep. The largest city in the path of the flood was Rexburg. As the flood swept into Rexburg it struck a logging mill on the outskirts of town and hundreds of massive logs were picked up by the powerful currents and became battering rams that smashed and destroyed buildings by the hundreds.

Figure 12. Teton Dam the day after failure, looking upstream. Note that the power station is completely buried. Source: Stamm, Gilbert G. (1976) After Teton: Reclamation Era, vol. 62, #3, Autumn, pp. 1-19

It took about 8 hours for the reservoir to empty. 35,000 people had to be evacuated. Hundreds of families had their homes obliterated. 14 people lost their lives either directly or as a consequence of the flood. Several thousand were injured. Irrigation canals that brought water to farms and crops were choked with debris and rendered useless; highways, railroad lines and power lines were damaged or destroyed; seven bridges were destroyed; cars, trucks, trailer homes and whole houses were swept away; an estimated 400,000 acres of farmland were inundated. An estimated 13,000 to 20,000 head of cattle were drowned and in the aftermath their corpses littered the flood pathway. The floodwaters cut a swath of destruction for some 80 miles along the Teton and Snake River valleys, from the dam site to American Falls Reservoir. Some estimates place the value of the flood damage as high as 2 billion dollars.

The devastation was extreme, as the following series of images demonstrates. Most of these images, unless otherwise noted, are part of the great collection of Teton Dam Flood photographs preserved by Brigham Young University, Idaho. Most of these images are from the Rexburg and Sugar City area and the flood path above and below these towns. Please take the time to peruse this gallery in an effort to get a sense of what this event was like from the perspective of those who experienced it and to appreciate the extraordinary power and force of water as well as the destruction that can follow in its wake.

Figure 13. The tsunami-like flood wave sweeping over farmland as it exits the Teton canyon and spreads out over the Snake River Plain. This doomed farm is about to be engulfed. Can one imagine the feelings of the family that sees this wave oncoming as they scramble to evacuate their farm to utter ruin?

Figure 14. The raging flood overtakes a farm which is in the process of being washed away.

Figure 15. Vast tracts of prime agricultural land were drowned

Figure 16. The swath of destruction reached up to 8 miles in width

Figure 17. Rexburg, Idaho after the flood. Rexburg lies about 14 miles southwest of Teton Dam. Brigham Young University (then Ricks College) in the foreground was elevated enough to escape flooding and was utilized by the Mormon Church to provide food and shelter to thousands of displaced and homeless flood victims.

Figure 18. Typical street scene in Rexburg as the flood surge passed through town

Figure 19. Rexburg scene, drowned neighborhoods, navigating streets by boat

Figure 20. The inundation of Rexburg

Figure 21. The flood passing through downtown Rexburg. Source: http://www.geol.ucsb.edu/faculty/sylvester/Teton_Dam/Teton%20Dam-Pages/Image16.html

Figure 22. Residents witnessing the drowning of their town

Figure 23. One hour to evacuate

AFTERMATH

The devastation left in the wake of the flood waters was immense. The following photos convey some extent of the damage.

Figure 24. A scene along the swath of destruction

Figure 25. One of many houses destroyed by logs swept up in the flood torrent

Figure 26. Many irrigation canals that brought water to thousands of acres of crops were choked with debris and rendered useless.

Figure 27. The flood left a massive, thick layer of mud and debris in its wake.

Figure 28. Whole communities were submerged and laid to waste

Figure 29. One of many houses swept off its foundation by the force of the water

Figure 30. Aftermath: The flood left thousands of tons of debris that littered the streets of Downtown Rexburg.

Figure 31. Aftermath: decimated neighborhoods, first the damage of the swiftly moving water followed by the deposition of a thick layer of mud over everything.

Figure 32. The amount of topsoil stripped away can be gauged from the separation of the railway from the post-flood ground surface.

Figure 33. The power of flowing water

Figure 34. A homeowner contemplates the wreckage of his house

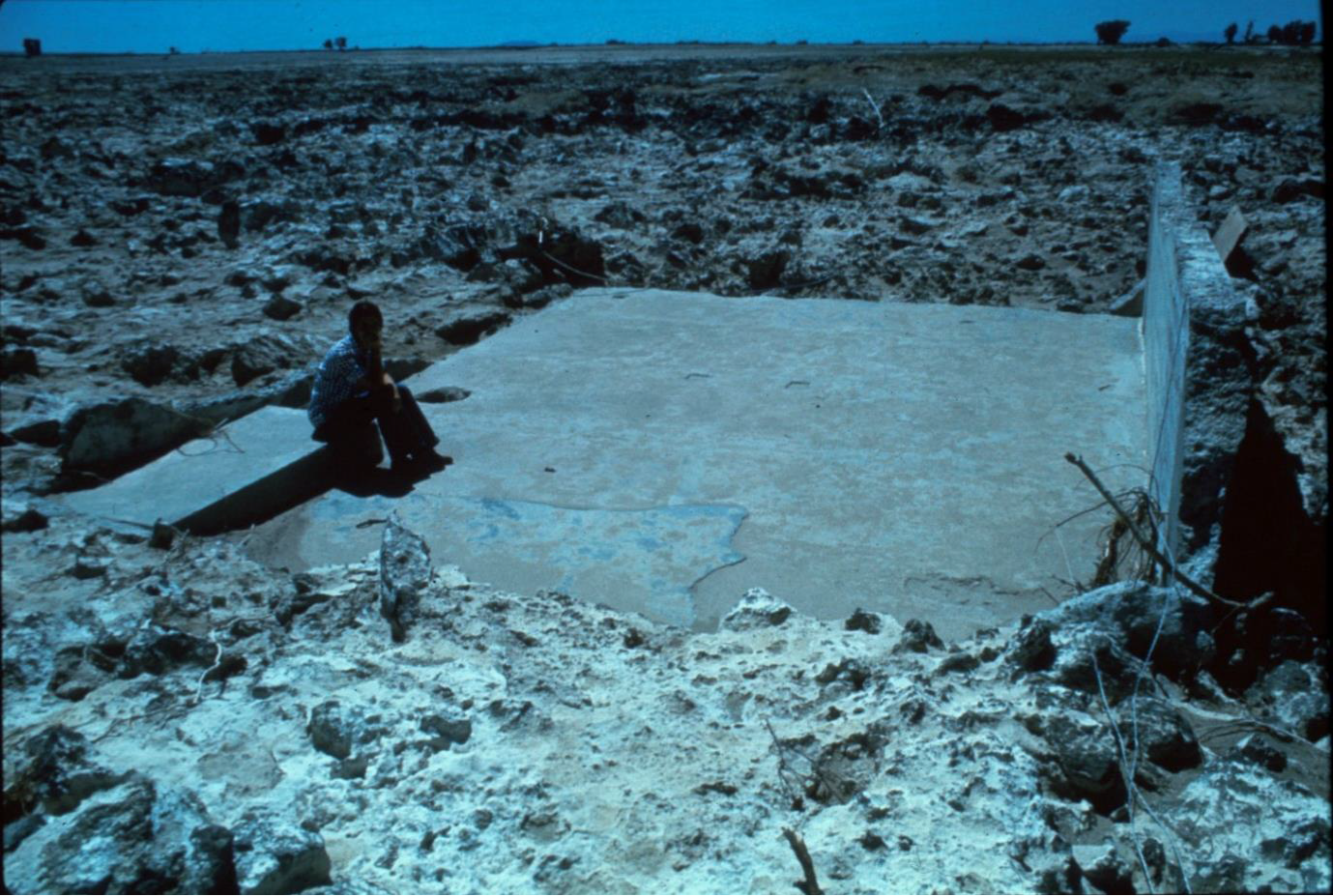

Figure 35. Desolation. A homeowner sitting on the step and foundation of what had been her house, utterly swept away by the torrent. Note the scoured and pockmarked character of the landscape.

Figure 36. All of the streets of Rexburg and Sugar City were covered with wreckage and mud

Figure 37. The flood caused massive damage to infrastructure

CAUSES

In the effort to understand the causes and origins of this monumental failure there were a number of conclusions arrived at by the various investigating committees. No final agreement was ever reached as to any single cause for the failure, but I think it obvious from the results of the various investigations that it was the unique confluence of factors that interacted cumulatively and pushed the system from relative stability to catastrophic instability. From the time of the first indication of a problem to the collapse was only about 5 hours. In his very useful reference on the failure of earth embankment dams Selected Case Histories of Dam Failures and Accidents Caused by Internal Erosion, author David Miedema presents 10 case histories of failure, including Teton Dam. In his summary of this event he presents the seven most likely mechanisms that may have initiated the failure. I won’t dwell on the technical details of the various failure mechanisms but Madiema sums up the general understanding that has emerged when he states “While the exact cause of the failure is not known, it is commonly accepted that a concentrated flow of high pressure reservoir water passed through open cracks in the rock upstream of the key trench on the right abutment and eroded the very erodible silt fill material, which was then carried into large open cracks downstream of the key trench.” The “very erodible silt fill material” is the aforementioned loess used for the core layer. The key trench referred to is, in this case, a large, roughly 70 foot deep slot excavated into the bedrock below both abutments that was supposed to act as an additional barrier to water penetration well below the mass of the dam proper.

As pointed out by F. Ross Peterson in The Teton Dam Disaster: Tragedy or Triumph? 95% of the people affected by the flood were Mormons whose presence in the Upper Snake River Valley goes back to the 1880s. In this semi-arid region the lifeblood of their farms and communities has always been water. Most Mormons in the area therefore favored construction of the dam. However, it was this shared heritage that dramatically lessened the severity of post-flood recovery efforts. Interestingly, as Peterson describes in the above referenced work, the “similar religious beliefs of the valley residents created an immediate folklore of premonitions, miracles and divine intervention.” This phenomenon is worth dwelling upon.

Utah University and Rick’s College (now Brigham Young University) compiled a comprehensive record of over 400 oral accounts of flood survivors. In these accounts there were many stories of people having prophetic dreams, visions and premonitions of disaster. In many cases property and lives were saved because people had the sense of foreboding, or a sense of some impending tragedy in the days leading up to June 5 and were psychologically or even physically prepared. It was appreciated by many that the timing of the dam break was fortuitous, occurring about noon on a Saturday. Had it occurred at night it would not have been discovered 5 hours before the collapse and instead of 14 lives lost there probably would have been thousands. As it was there was barely enough time to send out the alarm. Peterson remarks that because of their religious convictions many survivors and witnesses to the disaster believed there was a supernatural factor involved, and “As they analyzed the hours before the flood, some felt they had been warned by a premonition. Others felt that miraculous events accompanied the flood. To many, the entire disaster became an intense spiritual experience.” Peterson goes on to say that “All of these premonitions illustrate that numerous people felt that there had been a type of divine intervention on their behalf. The warnings of impending disaster or disruption came in a variety of ways, but the recipients, given time to contemplate the events of that week in June, were sure they had been warned.” Peterson provides the quote of one survivor that he describes as conveying the general feeling among many survivors: “I feel the timing of the break was miraculous because if it had been in the winter or at night, we would have lost a lot more lives. If the whole total dam . . . had crumbled away, we wouldn’t have a community or people in it. They couldn’t have escaped. It would have come so fast and so deep. That’s where I feel the divine intervention is.”

Let it be noted that great disasters of the past, both ancient and recent, frequently have such occurrences as premonitions and forewarnings associated with them. However one chooses to interpret such phenomenon it is too prevalent to be dismissed. Eyewitnesses and survivors of great disasters and calamities quite often interpret the experience in religious and/or apocalyptic terms. Peterson also relates stories printed in the local press that suggest another kind of unknown factor at work. The regional Logan Herald Journal reported on a particularly interesting event that occurred in the aftermath of the flood. Referring to a column by reporter Cleta Hansen, Peterson explains: “. . . when the flood waters receded, many people feared that the remaining ponds, pools, and stagnant water would become the breeding ground for mosquitos.” Health officials were rightly worried that this could provoke a serious health risk in the region on top of all the other devastation. However, as Peterson relates: “similar to what happened in pioneer Utah, thousands of sea gulls flew in from the southwest, settled on the water, gorged themselves with larvae, and the summer of 1976 was relatively mosquito-free.” Did someone send out a memo to this vast flock of seagulls that hundreds, perhaps a thousand miles away, a feast was awaiting them? We might justifiably wonder by what means this phenomenon was effected. The Mormons, as well as many locals, of course, attribute it to a miracle. I will only go so far as to acknowledge that Nature often works in mysterious ways.

Perhaps the most significant consequence of the disaster was the humanitarian response. Within several weeks of the disaster and over the summer some 40,000 volunteers arrived to help with the recovery. Ross Peterson comments on this phenomenon: “Another difference about this disaster was the fantastic volunteer labor force that literally invaded the area immediately after the collapse of the dam. In an unprecedented manner, over forty thousand volunteers performed clean-up work. Friends, relatives, neighbors, coreligionists, and total strangers came into the valley and worked under the direction of federal, state, local, and church authorities.” The people came from far and wide, from Idaho, Utah, Wyoming and Canada. Many were members of affiliated LDS churches. There were also many Mennonite and Hutterite volunteers as well as people who had no religious affiliation but who just felt the call to help.

The first task was “mucking out,” the cleaning up and disposal of several million tons of slimy, putrid mud that blanketed the region in the aftermath, mud that filled houses and basements, roads and irrigation ditches. Peterson relates how the impact of the massive clean-up and rebuilding effort cannot be appreciated by those who did not witness its progress. In the first week after the disaster 20 thousand volunteers arrived. On June 19th alone more than 5000 more showed up. They brought an attitude of optimism and cheerfulness that lifted the morale of the destitute and displaced victims. Work which would have taken weeks otherwise was completed in a matter of days.

When the call went out for 150 electricians, 400 showed up. Peterson quotes one of the electricians whose response was typical. After being told that he would be reimbursed by the church, he replied, “I didn’t come up here to be reimbursed for anything. I’ve got my truck and my crew and anything that needs to be done we’ll do it, and we’ll donate it and be happy to do it.” When the call went out for half a dozen front-end loaders Soda Springs responded by making up to 100 available. Peterson quotes one church leader who expresses the debt the flood victims owed to the volunteers, saying that they “literally lifted us up out of the mud and set us on our feet again . . . without them we never would have made it.” One woman survivor made a powerful and moving comment “I never wept a tear over the loss of our material things, but when I saw and felt the magnitude of the human heart, as it opened to our aid, I wept.”

Figure 38. Men, choose your weapons. Volunteers going to work

Figure 39. People of all ages came to lend a hand

Figure 40. Spontaneous cooperation in time of need.

A central creed of the LDS church is disaster preparedness. The efficiency of the family self-help and church operated welfare systems insured that almost no one went hungry. The presence of LDS owned Rick’s College in Rexburg with its dormitories and facilities insured that most of the displaced and homeless had shelter. As it was, the leaders of the church and the local government leaders were frequently the same people. The effectiveness of the locally managed and coordinated response left Federal agencies free to focus on restoring electrical power, and transportation and communication lines. General James Brooks who was Director of Disaster Services for Idaho, commented, “The church organization functioned marvelously under these kinds of conditions, and I’d have to say more effectively than most anything I’ve seen.”

The disaster that occurred was tragic enough in its own right. The floodwaters drowned some 80 miles of the Teton and Snake River valleys. But it could have been worse. A lot worse. The Teton River is a tributary to the Snake River. About 100 miles downstream from Teton Dam lay American Falls Reservoir along the Snake. This reservoir contains about a half cubic mile of water. In 1976 the dam retaining that reservoir was known to be severely deteriorated and in need of replacement. Officials rightfully feared that if a substantial volume of water rushing down the Teton River were to overwhelm American Falls reservoir, its old decrepit dam would probably fail, adding another half cubic mile of water to the flood. This augmented flood surge would then race down the Snake River Canyon about 30 miles until it reached Lake Walcott, held in by the Minidoka Dam. This dam would then likely fail adding the water of Lake Walcott and swelling the flood even further. Between the Minidoka Dam and the confluence of the Snake River and the Columbia River lay 8 more dams with their reservoirs. Officials and engineers began to panic as they realized the potential for all of these dams to fail one after another like dominoes. But that’s not all: along the Columbia between the Snake River and Portland, Oregon, lay another 4 dams with large reservoirs which likely would have been overtopped. Had this worst case scenario occurred it possibly could have been one of the greatest disasters of modern times, no doubt the greatest disaster in American history. In desperation officials raced to open the outlet works of American Falls reservoir full bore in an effort to drain as much water as possible before the flood torrent arrived. However, one of the same factors that contributed to the failure of Teton Dam in the first place now acted to mitigate the extreme disaster of multiple dam failures. This was the porosity of the rhyolite/basalt bedrock. By the time the flood surge reached American Falls it had substantially diminished in force and volume because much of the water had soaked into the highly permeable bedrock. American Falls reservoir was able to absorb the additional volume of water and an extreme calamity was averted. Two years later the dam at American Falls was replaced.

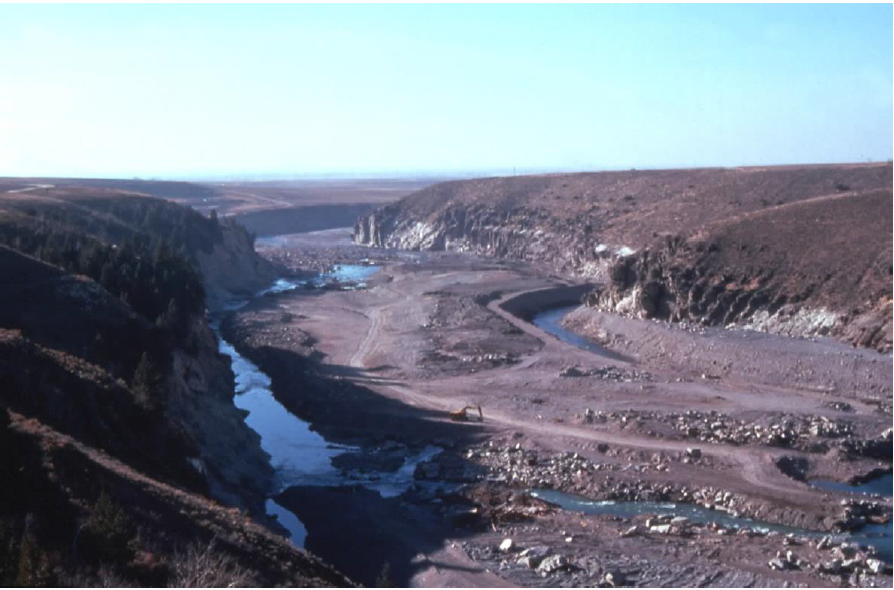

Figure 41. Teton Dam after failure, looking downstream. Note the obvious scouring along the lower section of the canyon wall, giving a clear indication of the depth of the flood. Source: Seed, H. Bolton & James Michael Duncan (1987) The Failure of Teton Dam: Engineering Geology, vol. 24, p. 178

Thankfully, that worst case scenario did not materialize. However, had it done so it would have imitated one of the massive floods that swept down the Columbia to the Pacific Ocean at the end of the last Ice Age. A scenario of multiple dams failing one after another as they are overwhelmed by an ever increasing flood volume might at first seem too extreme to be realistic, but even such a flood as that would be miniscule when contrasted with some of Nature’s mighty floods of the past. The deluges that came through the Columbia at the end of the last ice age were among the most massive floods ever documented to have occurred in the entire history of the Earth. The peak volume of flow through Wallula Gap, Washington was estimated by paleohydrologists to be on the order of 350 million cubic feet per second. A flow of such magnitude is nearly impossible to visualize, but for the sake of some kind of comprehension, consider this: a flood on this scale would utterly obliterate and wash away any major urban area in the world and leave nary a trace. New York, London, Paris, Hong Kong, Los Angeles, a flood of 350 cubic feet per second would erase any of these cities as if they had never existed within a span of about one to two hours. Paleohydrologist Victor Baker, PhD. has estimated the flood current that swept through Spokane Valley in Washington State was on the order of 700 to 800 million cubic feet per second, or about twice as great!

What do we really know about the cause, or causes, of such inconceivably huge floods in the recent geological past?

What do we know about the extent to which human societies of the time, or, dare I say it, human civilization, was affected by gigantic floods, especially as we come to realize that the mega-flood phenomenon was global in extent? The lessons learned from the study of modern cataclysms, even though these are diminutive by ancient standards, can nonetheless provide valuable insight toward understanding and identifying those mighty deluges and catastrophes of the past and deciphering their fingerprints in the modern landscape.

But what do we know about the process that led to the Teton Dam disaster? We have discussed some of the technical aspects, the engineering and geological factors leading to collapse, but there is the other dimension of failure that must be addressed: The human factor.

In his study Selected Case Histories of Dam Failures and Accidents Caused by Internal Erosion, civil engineer David Miedema discussed the issue of ultimate causes. He pointed out that “Geologic factors, design decisions, construction control, and human factors were all part of the story.” In regards to the “human factor” Miedema cites the conclusions of engineer James L. Sherad, whom I quoted above, who argued that there was one common denominator directly or indirectly associated with the all the various factors contributing to failure and that was what he called “the bureaucracy problem.” In particular Sherard criticizes the decision to suspend grouting operations.

“The decision to abandon the gravity grouting was surprising. The gravity grouting was not a very conservative method of sealing the cracks but it was much better than doing nothing. I believe that there will be no strong argument with the opinion that it was completely unacceptable practice to stop the gravity grouting . . . I believe this blunder can only be explained as the long time result of bureaucratic restrictions on the USBR staff. The abandonment of the gravity grouting could only have been permitted because the individuals in the design group who would have known to insist on the continuation of the gravity grouting were separated from the decision.”

The effects of bureaucratic impediments to efficient and competent practices were not limited to decisions regarding grouting procedures but also encompassed restrictions upon engineer’s ability to study ongoing projects first hand in the field. “Travel to sites for design engineers was considered generally unnecessary and was frowned upon. The responsible design engineer for major USBR dams frequently never visited the site, either in the design stage or during construction. At periodic fairly regular intervals, usually following federal elections, all ‘unnecessary travel by federal employees’ was banned by fiat from Washington. As a result, the designer was sheltered from problems and experience.”

Sherard points out that the agency suffered from “inbreeding” and was resistant to independent review and analysis by various specialists. In addition, there was a lack of cooperation between the construction supervision staff and the design group. It was believed that the resident engineer on the project should not need to consult with the design staff and that frequent consultation would reflect negatively on the resident engineer’s advancement. He concludes by saying that “Decades of such bureaucratic restrictions and inbreeding led to the situation in which the Teton Dam was constructed according to a design which would have been considered unacceptable by independent specialists.”

This example should serve as a warning and a reminder to all those who advocate for the continued expansion of government and bureaucratic power at the expense of private initiatives that can be held accountable for their failures. The pre-eminent question becomes: How do we restore accountability to government? Thomas Jefferson undoubtedly had it right when he advocated for a government “rigorously frugal and simple.” Is such an ideal out of the question in the 21st century, or is there another way of conducting the business of our civilization than the continued centralization of political power?

Russ Brown was one of the original opponents of the Teton Dam project. He closely followed the events leading up to the failure and the post failure response by various entities and doesn’t mince words when it comes to assigning responsibility. His analysis of the situation needs to be pondered by anyone who desires a realistic assessment of the causes and consequences of this calamity. He penned some remarks for the website of Idaho Public Television in which he clarifies the political context that led to the disaster. He does not moderate his criticism of the forces responsible. The title of his missive is “The Teton Dam Disaster, A Product of Three Failures of Government Institutions.” His trenchant comments lay bare the core of mendacity, vested interests, and political machinations that reached their culmination in this tragic event.

“The roots of the Teton Dam project were greed and tradition. The greed of irrigation interests had been a tradition for almost three-quarters of a century; it was a type of socialism that was attractive to nominally conservative Western farmers. The opportunity to get Federal money for personal enrichment was always a sufficient reason to make the welfare state socially acceptable.”

“As ever, that lust for a handout was facilitated by elected officials at both the State and national level. Pork-barrel projects are the life-blood of politics; they serve the principal objective of almost all Western Senators and Congresspersons, i.e., getting re-elected. Pork has the added advantage of being bipartisan. With few exceptions, Republicans and Democrats cheerfully belly up to the trough. Environmental considerations are not even in last place when such projects are considered; they are out of sight.”

“The Bureau of Reclamation did everything that it could to serve the pork-barrel constituency. Project justifications were enhanced by overstated benefits and understated costs. In private industry, the Bureau’s practices would have been met with disbelief, occasional laughter, and indictments for fraud. In the industry of government, it produced nothing but happy faces and fat cats. Congressional passions were the Bureau’s commands. Questions were socially and politically unacceptable. . .”

“The matrix of deceit in the Teton project included inflated benefits for irrigation and flood control and a myriad of deflated or omitted costs. IRRIGATION: Benefits claimed for 37,000 acres–20,000 were already irrigated.”

“Benefits calculated by comparison to the worst drought years in the history of the area. (1931-1937) Although 70% of the cost of Phase I was allocated to irrigation, the irrigators would have paid less than 10% of the cost.”

These remarks are only part of his complete statement, which can be found here: http://idahoptv.org/outdoors/shows/bofr/teton/brown.html

The benefits of the project were exaggerated and the costs were deflated or omitted altogether. This is an all too familiar pattern. It is to be noted that here is one example among too many to count, of politics corrupting money. The socialist left has it exactly backwards—it is not money that corrupts politics—it is politics that corrupts money. The whole process of wealth centralization in the hands of government, that is, in the hands of politicians and bureaucrats, who then dole it back out to the States and the private sector with political agendas grafted on is the basis of most corruption in America to some degree or another.

The Time Magazine article I quoted from above concludes with this paragraph: “Whatever the investigations turn up, they will do little to ease the tragedy for thousands of farmers and townspeople. Even with help from Washington—and Idaho Governor Cecil Andrus says that “liability is clearly at the door of the Federal Government”—it will be years before the communities downstream from the ill-fated dam can completely recover from their losses.”

The fate of the people in the headwaters of the Teton River was taken out of their hands and placed in the hands of distant bureaucrats in Washington D.C. The people suffered mightily for this loss of autonomy. In spite of warnings from geologists about the problematic nature of the site, including the possibility of seismic activity, the Bureau of Reclamation proceeded in a manner that can only be described as reckless. Their report submitted to the newly created EPA in 1971 was 14 pages in length and made no mention of potential problems resulting from seismic activity or bedrock permeability. Approval for the project was given, funds were allocated and the decision to proceed was made before any test-well drilling was conducted and before excavation revealed the presence of fissures and fractures throughout the wall of the canyon. By the time the problems became apparent political momentum was already propelling the project forward with no turning back.

As far as asking the critical questions, the ones that were considered socially or politically unacceptable in regards to the Teton Dam, one can’t help but think of the reaction to those who question the politics behind the global warming/climate change debate, where the customary tactic for the pro-global warming side of the debate is to label anyone who questions the so-called “consensus” of officially approved, big government climate science a climate change “denier,” as if such a thing actually existed somewhere out there in the real world. Then to make sure that any unacceptable questions or criticisms are further silenced, dismissed and ignored, the deceit of big tobacco company lawyers is regularly invoked with the intention of creating a stifling smokescreen that obscures and precludes any further discussion. The developments that have led to this unacceptable state of affairs had their precursor in the mind-set that led to the Teton Dam disaster. In both cases the process was, and is, dominated and directed by political agendas.

We cannot reverse the course of history. The dam failed, people suffered, and then picked up the pieces and moved on with their lives. Two generations have passed since that fateful day. Only the locals remember it now. The most valuable thing that we can do now is to learn from the experience. As a result of the failure of the Teton Dam a large flood of water was released across the landscape of southern Idaho and it left a series of very distinct effects that are still apparent today. We also have a mass of data regarding peak discharge, the total volume of water released, the timing of the flood surge, the draining of the reservoir and the erosional and depositional effects upon the landscape. A careful consideration of the this disaster can, therefore, yield insight into a number of questions, most importantly into a deeper understanding of events of the past involving floods several orders of magnitude greater than the Teton flood and their effects upon human culture and upon the land. Such knowledge would contribute significantly to our understanding of ancient history as well as providing a knowledge of history that may well prove crucial to the future of human civilization on this planet.

The effects of water erosion and deposition tend to be scale invariant, that is, the phenomenon associated with these processes, whether at a small scale in the hydrological laboratory or larger scale at the level of the landscape, display the same forms and patterns. By analogy to these patterns at the micro- and mesoscales we can comprehend and visualize patterns at the mega-scale that would ordinarily be beyond the range of perception without technological augmentation. It is these mega-scale forms and patterns that convey awareness and knowledge of extreme catastrophes of the past, manifesting on a planetary scale, and of the implications of these events for understanding not only the progress of life on Earth but the progress of human civilization as well, not only in the past but in times to come.

What these patterns teach us is that this planet is exceptionally dynamic and undergoes two modes of change: that which we have experienced in modern times: the gradualistic, uniform pace of change slowly manifesting upon the global landscape as it constantly and steadily evolves in response to the relatively mild, protracted forces of nature operating under normal circumstances, and then there is the other mode − the short-lived episodes of rapid, extreme change − when the driving forces of geological, environmental and climatic change are increased by orders of magnitude. It is this level of catastrophic, natural change that the human race has not yet come to terms with.

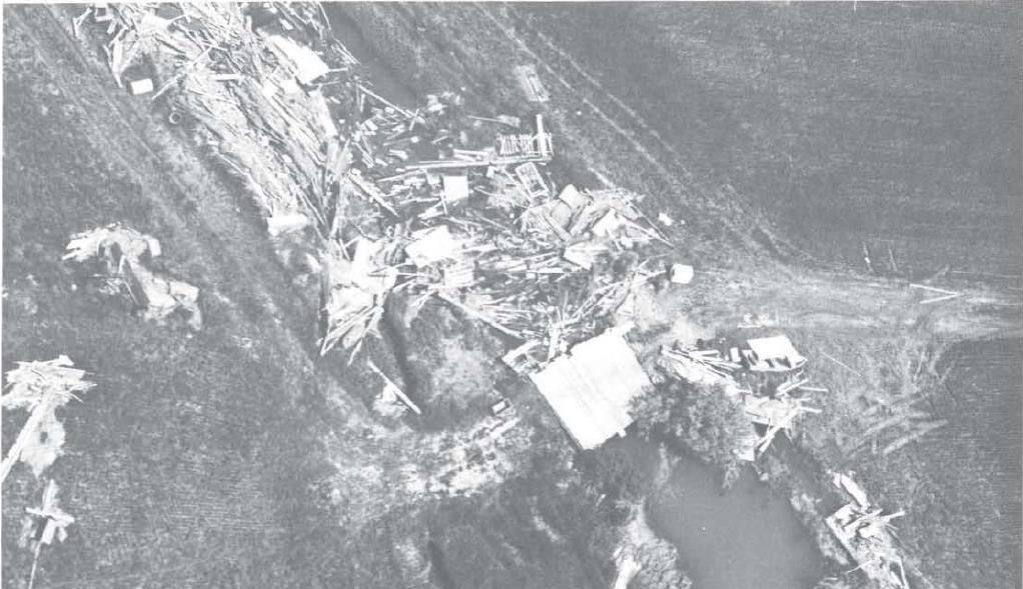

Figure 42. View of the canyon below the dam taken in 1977. The Teton River has cut a new channel through the massive flood debris that chokes the canyon floor. This debris is composed of the roughly 4 million cubic yards of dam material that was swept downstream by the discharging flood waters. Scouring and erosion on the canyon walls from the passage of the flood torrents is readily visible. These features can yield insight into the great diluvial catastrophes of the past.

There is another important lesson to be learned from this particular event: a well prepared, self-reliant people spontaneously, voluntarily and harmoniously rose to the challenge, came together to alleviate the worst excesses of the disaster, to render aid and assistance, and to provide food and shelter to thousands of victims. It must be acknowledged that local, state and Federal officials responded effectively as well. But it must also be recognized that the ethos of government was even then undergoing decline, as evidenced by the failure of the Teton Dam project itself. Nevertheless it still retained enough individuals endowed with the traditional values of honor, self-reliance and government as servant of the people to rise to the demands and challenges of the occasion. And, it must also be recognized that the deterioration and bureaucratization of government has continued apace since then and as it has expanded in scope and power it has declined in efficiency and accountability. This was clearly demonstrated by the incompetent Federal response to Hurricane Katrina. The unwieldy bloated government of today is not the government of 1976, which, even then, had reached well beyond the point of diminishing returns, that point at which the cost of government exceeded the value of its benefit to the society which it presumes to govern.

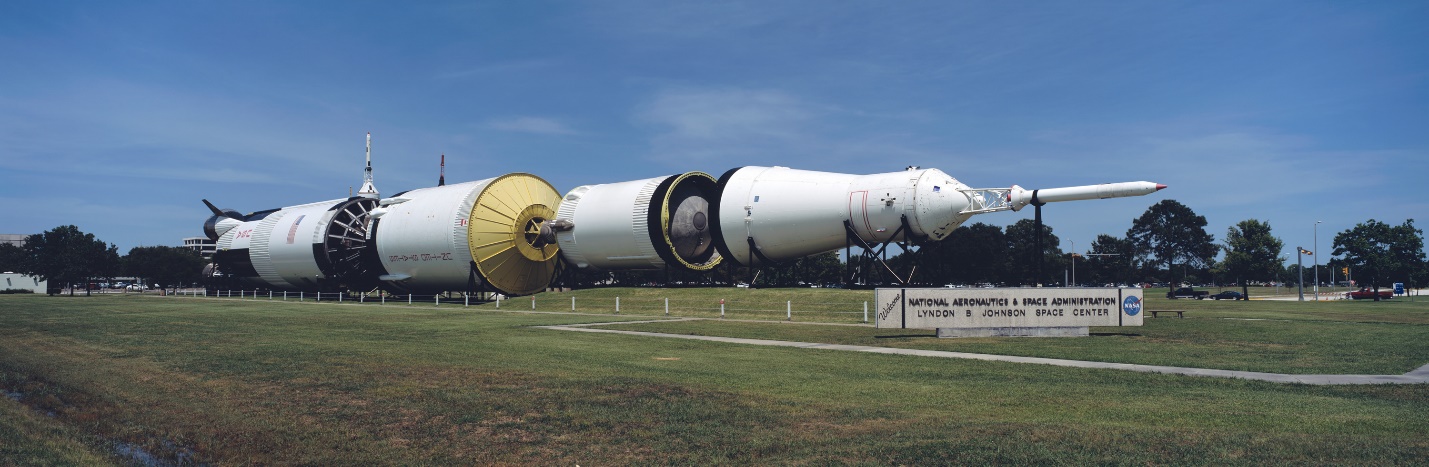

It should be noted that funds appropriate for the challenges of this project, and the strenuous effort and impeccable performance required to build a structure that would have endured, were insufficient. This resulted in attempted cost saving measures that, ultimately, proved to be fatal. The great infrastructure building era in America was over with the failure of the Teton Dam, whose ruins still stand as a testament to the collapse of a grand political experiment almost exactly two centuries after it was first inaugurated. The failure of this dam is an apt metaphor for the failure of the original vision of a free people in control of their own destiny and its replacement by a bloated, unaccountable political bureaucracy that is no longer capable of fulfilling the function for which it was created. The funding shortfall that compromised the Teton Dam project to the point of failure also contributed to the termination of the Apollo Space program, both of which were sacrificed on the altar of the wretched Viet Nam War as it drained the national coffers in the pursuit of imperial dominion. The ruin of the Teton Dam that still stands, is perhaps analogous to the great rusting ruin of one of the last 3 remaining rockets of the mighty Saturn fleet that was stored at the Johnson Space in center in Houston in 1977, where it lay, on its side, exposed to the elements for nearly 30 years. But no matter, the politicians, government officials and bureaucrats are seldom, if ever, held accountable for their mistakes and misdeeds, and always pass the bill for their blunders on to the taxpayers of America.

Since 2007 the mighty Saturn V rocket has been restored and is now housed in a special building still at the Johnson Space Center. While it is commendable that the rocket has been restored and protected from further deterioration, it is lamentable that it is not carrying astronauts to the moon, and that it is now a relic of history only serving to remind us of a heroic, unfinished enterprise prematurely terminated in its infancy by a failure of vision and will.

Figure 43. A section of a Saturn V rocket booster at the Johnson Space Center.

Meanwhile, across this land the remains of the great infrastructure building era in America are aging fast. Bridges are rusting; roads, highways and levees are degrading; water and power distribution networks are deteriorating; dam reservoirs are silting up, and over 2000 dams are considered at risk while another 2000 are considered deficient, according to the conclusion of a 2009 case study conducted by the American Society of Civil Engineers. That same organization has estimated that in order to maintain the infrastructure of this nation we will need to spend an additional $1.1 trillion by the year 2020 or face both increasingly severe economic costs to all sectors of society and the increasingly dangerous consequences of infrastructure failures. We have seen the potential consequences of the neglect of our national infrastructure with the failure of the levy system in New Orleans in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, which amplified the severity of the storm surge far beyond what it would have been had the levees performed their function as intended.

To belabor a point, while the challenges facing America require a vigorous and flexible response for their resolution, the ability to respond is being increasingly hampered by the continued expansion of a top heavy, unaccountable, administrative and regulatory bureaucracy. Along with this goes a long entrenched and thoroughly misplaced sense of national priorities that consume the national treasure with no discernable benefit accruing to society and the regrettable increase in dependency on the authoritarian state and self-serving political elites, all the while spending the billions we need to restore our national infrastructure on the destruction of the infrastructure of other nations. And, for everything we destroy to perpetuate the imperium additional resources must be extracted from nature and additional energy must be consumed to rebuild, restore or replace the destruction.

Yes, there are many lessons to be gleaned from the Teton Dam disaster, human related and otherwise. In an event such as this we are privy to a diminutive echo of the great planetary disasters witnessed and survived by our ancestors − mega-disasters which have occurred with such startling frequency through the long course of prehistory and history that we would be seriously remiss should we fail to understand them, their cause, their effects, and how ancient peoples might have survived and coped. I will be devoting future articles and essays to a discussion of this critically important issue.

We stand at a historical crossroads. Will we learn in time to reverse the course of decline that has plagued civilizations since history began? Will we recognize or will we disregard the ruin and wreckage of former worlds that surrounds, encompasses and underlies our present civilization, the debris out of which we have literally constructed our modern world? Can we read its message and respond accordingly? How, in fact, should we respond to the knowledge that in the time that we modern humans, homo sapiens sapiens, have walked this planet, as many as a dozen extreme global scale mega-disasters may have occurred that would be fully capable of bringing down the curtain on modern civilization and sending humanity straight back to the Stone Age? Is it important that we understand the causes and timing of these great catastrophes that regularly interrupt the forward momentum of the world?

Is the spirit of charity, spontaneous organization and hard work that inspired and motivated the actions of those thousands of volunteers in the face of disaster still possible today? Will we pass into oblivion as a nation and as a civilization, or ascend to unimaginable heights of achievement, triumph, and possibly even glory? The outcome of this question will come down to a matter of priorities and will. A future of unlimited possibilities is within our grasp if we prove to be worthy and well qualified and willing to seize the opportunities before us.

REFERENCES AND SOURCES

Peterson, F. Ross, “The Teton Dam Disaster: Tragedy or Triumph?” (1982). USU Faculty Honor Lectures. Paper 7. http://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honor_lectures/7

Rogers, J. David ( ) Retrospective on the Failure of Teton Dam Near Rexburg, Idaho June 5, 1976. Retrieved from:http://web.mst.edu/~rogersda/teton_dam/Retrospective%20on%20Teton%20Dam%20Failure.pdf

Seed, H. Bolton & James Michael Duncan (1987) The Failure of Teton Dam: Engineering Geology, vol. 24, pp. 173 – 205

Sherard, James L. (1987) Lessons from the Teton Dam Failure: Engineering Geology, vol. 24,

pp. 239 – 256

Smalley, Ian (1992) The Teton Dam: rhyolite foundation + loess core = disaster: Geology Today, Jan.-Feb. pp. 19-22

Solava, Stacey & Norbert Delatte (2003) Lessons from the Failure of Teton Dam: Forensic Engineering, vol. pp. 178 – 189

Stamm, Gilbert G. (1976) After Teton: Reclamation Era, vol. 62, #3, autumn, pp. 1 – 19

Stene, Eric A., (1996) Teton Basin Project, Bureau of Reclamation. 31 pp.

Time Magazine (1976) TETON: Eyewitness to Disaster: June 21, vol. 107, #26, p. 74